History of Turkish Ceramics (Çini, Tile Art)

Çini is a kind of ornamentation art, mostly a mixture of architectural ornaments, daily use items or objects for decoration purposes. They are shaped objects from mud which is usually kaolin, quartz, clay and feldspar mixed with a certain amount of water. These products are fired in high-grade ovens, also called bisque firing. Then the patterns prepared by traditional methods are applied with the help of a brush on the bisques with some raw materials and colorized oxides. In order to protect these designs and make the surface smoother, the diluted raw material mixtures are ground in much finer grain sizes and then applied on the first fired decorative body. After, they are fired for the second time. This firing is also called glaze firing. The patterns between the bisque and the glaze can be preserved for hundreds of years.

History

Famous traveller Evliya Çelebi mentioned Çini in his book “Seyahatname“, reporting about the beauty and unicity of the Çini articles manufactured by local Kütahya artists in 17th century. Historically the ceramic manufacturers have been producing work in Kütahya since the Phrygian period and continued with çini-ceramic works made with red paste material in the last half of the 14th century. In the late half of the 16th century, Iznik çini art reached its brightest period. In the years after however, İznik manufacturers were severely damaged since they lost the support of the palace and the production of Çini almost ceased to stand.

Initially, Kütahya çinis were produced to meet the needs of the local people and with a more modest quality level compared to the Iznik çinis that were produced. As a result of this situation, the designs of the motifs were arranged and formed with more density. The Çini products were filled with dense motifs and patterns to hide the mistakes and dull background color. In this way; they aimed to mask the quality deficiencies that occur in the çini bisques, the glazes and the colors with intensive pattern designs. The need for intensive pattern designs is one of the most basic features that reflect the characteristic structure of Kütahya çinis. The solution, which emerged as a necessity, was to enrich the motif and pattern designs and increase the aesthetic qualities.

One of the most important problems that the çini producers are facing is; the motifs and designs that directly affect the sale of Çinis are not rich and sufficient in quality and quantity. Therefore, the production of Çinis that are decorated with similar motifs and designs threaten the domestic and foreign markets. Re-interpretation of Çini motifs and patterns went from a contemporary perspective without straying away from the original; it is important to save the Kütahya Çini art which has been going on for hundreds of years from repetition and copies, and to determine a new route in its original line. For these reasons, there is a need for real artists who have internalized the characteristics of Kütahya Çini art.

Turkish Ceramics / Çini Art

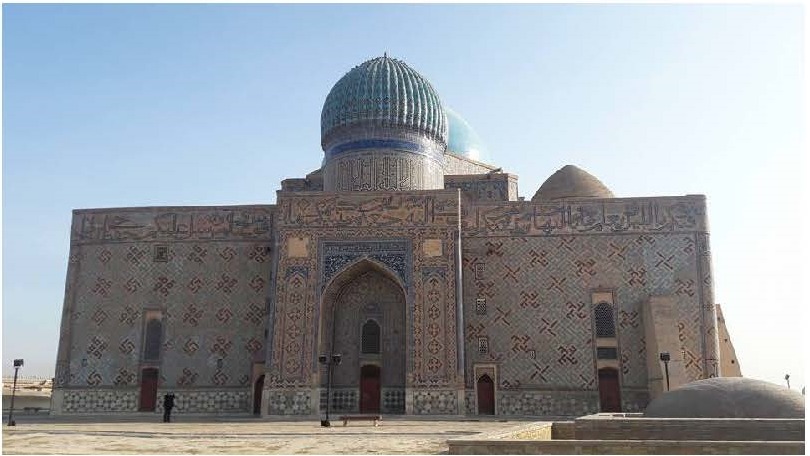

It is acknowledged by the art history specialists that Çini is an art unique to the Turks. Turks first manufactured Çini in Central Asia. The oven residues and çini fragments that were found in excavations in Kashan, Turfan, Aşkar and Koça areas in Central Asian territories indicated that there was such type of pottery art which the Turks consider as traditional artifacts from before the 8th century. The city of Kashan in Central Asia, which is thought to be the Çini production center of the period, created the “Kaşi” used in the architecture until the 18th century and the other used products (such as plates, vases, bowls, etc.) were named “Evani”, standing for pots and pans.

The fact that the word “Çin” means the word “China” in Turkish, was changed by the Ottomans to “Çini”, adding an „i‟ just to separate the differences in the pottery manufactured by each country‟s potters. Yet, due to the good reputation of the porcelain imported from China starting from the 18th century, the word Çini was preferred instead of Kaşi for commercial reasons. Çini was first properly used in Turkish literature and scriptures in 1958 by Prof. Dr. Hakkı İzzet.

Çini art was moved to Anatolia by the Seljuks and reached its peak in the centers of Bursa, Istanbul, İznik and Kütahya during the Ottoman period. In the following periods, Kütahya became one of the two most important çini centers in Anatolia together with Iznik. Since the manufacturers of Iznik were under the protection of the Ottoman Palace, they had the highest level of possibilities both in the bisque firing and design of the çini.

Decoration in Çini Art

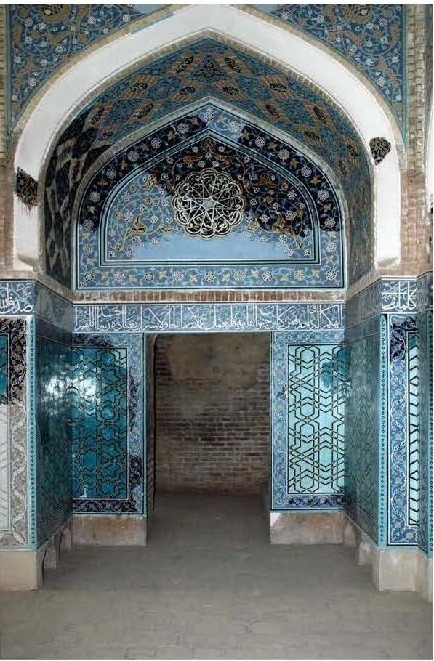

As a general acceptance; all products obtained by kneading and shaping of non-organic raw materials with water in certain proportions are called ceramics. When evaluated in this aspect, the Çini is actually a kind of ceramic. However, the distinctive feature of Çini products is the decorations made under the glaze with brush. Decor; it can also be considered as an in other wordsof the pattern integrity created with unit motifs. These decors can be preserved for hundreds of years by being confined between the structure and the glaze. From the moment it was made, it is the main reason why Çini is considered as a branch of art as it is able to carry its social values, social-cultural structure, beliefs and aesthetic perspective beyond centuries.

Turkish society is a society that has managed to maintain its existence in different states and different flags in almost every stage of human history. The continuity in history has brought with it the opportunity to establish a rich culture and civilization. Since the first finds of the Pazırık Kurgan, the Turks have depicted scenes, beliefs, social value judgments and imaginary worlds reflecting their daily lives by symbolizing the beauty perception of their periods and produced different works of art throughout the history.

It was the material culture data of the Turks, which documented the historical past of Turkish societies dating back centuries. The earliest of these finds are mine, stone and ceramic-çini. The inscriptions, miniatures, embroideries, pieces of cloth, Çinis, which are in the center of the Uighurs called Karahoço, are among the important examples of Turkish culture and art.

Although the first information in the historical sources of the Turks is found in Chinese and Arabian sources, the oldest artifacts found to have belonged to the Turks date back to 2500-3000 BC. These artifacts include stone, metal, ceramics, Çini, pieces of fabric, rock paintings, sculptures, as well as numerous artifacts made by the Turkish states that have managed to survive without interruption throughout history.

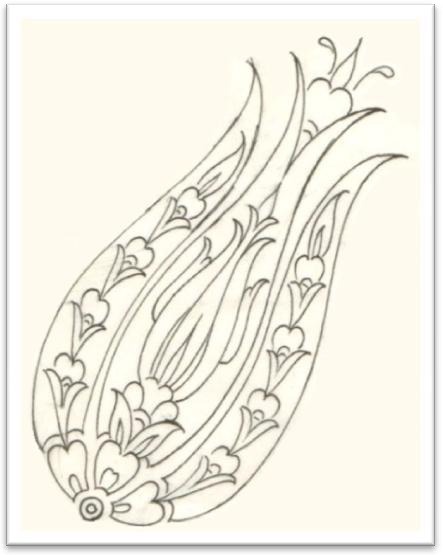

Turks, who generally have a nomadic lifestyle, used the figures of human figures in the decoration of works of art, the wild animals and natural phenomena they frequently encountered in their daily lives, especially in the death and burial ceremonies. On the other hand, after the acceptance of Islam by the Turks, the use of the human figure, which was frequently seen in Turkish artworks, left the place of Islamic art in herbal and geometric motifs and patterns. As it is understood from this point, similar processes in other societies, such as life style, beliefs and aesthetic perception of Turkish society, are the determinants of the design of motifs and patterns which are the main elements of the works of Turkish societies.

Although the art of Turkish art has spread to a very wide area from its birth to the present, it has largely preserved its cultural and artistic characteristics. In their journey from Central Asia to Anatolia, the Turks carried along with the elements of the cultures and civilizations of the other nations in the Central Asian basin, as well as their accumulations, which were synthesized by the effects of Islam. Without losing its national identity, Turks, who bring together the values they have received from different cultures and their social characteristics in harmonious designs, have a rich cultural heritage in this sense.

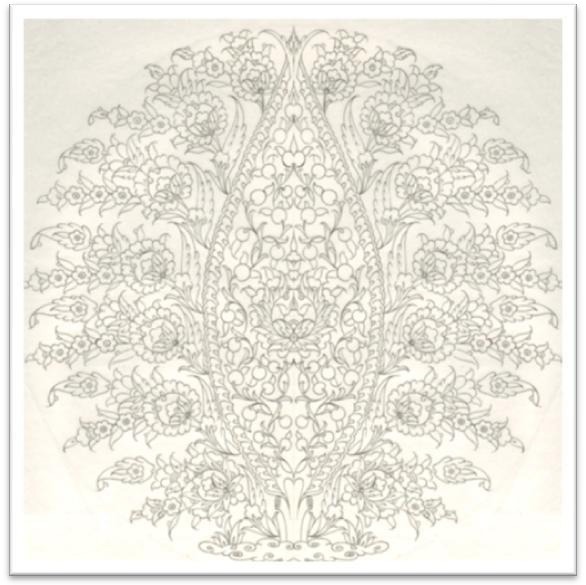

For thousands of years, Turkish culture has succeeded in expressing its emotions, thoughts, beliefs, tastes and desires with an aesthetic perception on a universal level. The most basic issues that determine the design of motifs and patterns are the social moral rules, lifestyle, tastes, desires and wishes that the designer has affected as a result of cultural accumulation. The starting point of these designs is sometimes natural phenomena such as natural phenomena, animals, flowers, trees and other plants, and sometimes they are the geometric lines used as the means of expression of abstract concepts. However, the designs of the motifs and patterns designed by the Turks are in any case equipped with a meaning load.

(Represents the bond connecting the life of the worldly and the hereafter)

References: Çini Artist Hamza Üstünkaya, 08 November 2010, Kütahya/Turkey

(Tulip Motif represents the unity of God in İslamic mystical thought) References: Çini Artist Hamza Üstünkaya, 07 February 2013, Kütahya/Turkey

(Carnation Motif represents spring, nature awakening, renewal.)

References: Çini Artist Hamza Üstünkaya, 19 July 2009, Kütahya/Turkey

Traditional Kütahya Ware (Also Known as Çini)

Çini is the symbol of Kütahya and at the same time introduces to the whole world an important art branch as well as the livelihood of Kütahya. The ceramic manufacturers have been producing work in Kütahya since the Phrygian period and continued with Çini-ceramic works made with red paste material in the last half of the 14th century. The motifs and colors of the Çini in Kütahya made during this period were similar to the Iznik çini. In these first examples, cobalt blue, manganese purple, turquoise and black colors were mainly used. The colors that were used had darker tones than the ones used in the Iznik works yet the features were similar to the Anatolian Seljuk Çini ornaments. The transition from red Çini and ceramics to blue-white manufacturing began in Kütahya at the same time as İznik in the middle of 15th century. Instead of red bisque, a new style was created with white, hard bisque bearing porcelain-like blue-white Çini and ceramics.

In the late half of the 16th century, Iznik Çini art reached its brightest period, with work that was developed with vivid and radiant colors. When the characteristic features of Iznik çini art are examined, one can see that the quality structure of the work, which is called “Sclera” (white part of the eye), give off a more homogeneous and clear white background. With this technique, the motifs and patterns have a much more striking and brighter appearance. With this in mind, to show the quality of the white background, the motifs and patterns were made with more plainness. In the years after however, Iznik manufacturers were severely damaged after the loss of support from the Palace (at the end of WW1) and the production of Çini almost ceased to stand.

Evliya Çelebi, who is a famous traveller from Kütahya, mentioned Çini in his book “Seyahatname”, reporting about the beauty and unicity of the Çini products manufactured by local Kütahya artists in 17th century. In the 18th century when the art of Iznik was completely lost, Kütahya ateliers gained momentum with the withdrawal of Iznik and developed a brand new style of art as a result of free brush use and more modern approaches.

Since Kütahya Çini manufacturers did not receive great support as the Iznik did in any period of history, the manufacturers in this region followed a more humble line. Initially, Kütahya Çinis were produced to meet the needs of the local people and with a more modest quality level compared to the Iznik Çinis that were produced. As a result of this situation, the motif designs were arranged and formed with more density. The Çini products were filled with dense motifs and patterns to hide the mistakes and dull background color. In this way; they aimed to mask the quality deficiencies that occur in the Çini bisques, the glazes and the colors with intensive pattern designs. The need for intensive pattern designs is one of the most basic features that reflect the characteristic structure of Kütahya çinis. The Solution, which emerged as a necessity, was to enrich the motif and pattern designs and increase the aesthetic qualities.

These tiny pieces of Çinis made of hard white clay are put under the glaze technique, then made into small sized elegant works such as cups, bowls, pitchers and plates etc. These items all carry a different local artistic character from each classical style with light brush strokes. They are decorated with small flowers, plant motifs, leaves, vines, raindrops and medallions with light blue, navy blue, red, yellow, purple, green, and lilac colors. Besides these, lifelike birds, fish and local outfit designs were widely used. However, in the second part of the 18th century, the quality of Kütahya’s Çini had deteriorated in terms of color, motif and shape. This dreadful period lasted a long time. In 1905, the governor, Fuat Pasha, had the government building decorated with Çinis. Then later wrote in a report to the center saying; “Three centuries ago in Kütahya, there were more than three hundred Çini manufacturers. In 1795, the number of manufactured Çini ateliers had fallen. Towards 1902, Hafız Emin and Hacı Minasyon’s ateliers had closed down. During the Second World War, Çini manufacturing in Kütahya was revived once again in response to the need and continues its development today.

Kütahya is the only city in Turkey that has earned importance in statistics today with its commercial and artistic contribution to Çini culture, aesthetic line, continuous developing production, technology and globalizing world markets since the beginning of production start in the 13th century. Despite this, it cannot be denied that negative factors such as commercial expectations and inadequate academic training have led to a great decrease in the art of Çini and its industry. The characteristics of the Çini products that started to rise from the 16th century have fallen due to the 19th century national and sectoral negativities. The Çini sector, which has gained a momentum with the Republican era, has now become more intense and has achieved a significant success level in the area of quality and standard as the concomitant result of increasing research-development and product-development studies.

However, in order to meet the anticipation of globalized domestic and foreign markets, handiwork shifted to technology-intensive production as it is a lot quicker. The inability to fully hold the academic balance of the traditional master apprenticeship has resulted in a decrease in quality in design as well as aesthetics. The quality and standards that are captured in the production of Çini structure are unfortunately not current for Çini motifs and patterns production due to the lack of trained artists and masters. In today‟s Çini motifs and designs, it is not possible to talk about innovation when we compare them to the motifs and designs in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as there is no extreme change in design. Due to commercial concerns and lack of academic publications and research, the Çini sector has not gone beyond the repetition of old motifs and patterns.

Conclusions

One of the most important problems that the Çini producers are facing is; the motifs and designs that directly affect the sale of Çinis are not rich and sufficient in quality and quantity. Therefore, the production of Çinis that are decorated with similar motifs and designs threaten the domestic and foreign markets.

Re-interpretation of Çini motifs and patterns went from a contemporary perspective without straying away from the original; it is important to save the Kütahya Çini art which has been going on for hundreds of years from repetition and copies, and to determine a new route in its original line. The most important feature that distinguishes Çini products from other ceramic products is the decorations applied under the glaze. The term of decor can also be referred to as pattern integrity created with unit motifs.

Çini art is one of the oldest art branches of Turkish history. It has been continuously produced until the present day because it can survive for years and can deliver its social values to future generations. Çini artifacts have also been used frequently in religious buildings and state-owned public buildings, because they make it more aesthetically valuable.

Çini Art lived its most spectacular days in the Ottoman Empire during the 15th and 16th centuries. İznik and Kütahya stand out as the two most important Çini production centers in this period. At the end of World War I, Iznik Çini production, which lost its support of the palace, has losed its importance in the following years. This situation has brought Kütahya Chineseism to an even more important position. Today, the most important and even the only representative of the Turkish Çini Art, Kütahya Çini sector is experiencing a blockage due to repetition and copying in motif and pattern design despite the increasing technical possibilities. For this reason, it is necessary to reinterpret today’s Turkish society with the contemporary aesthetic point of view in accordance with the original of the Çinis and patterns. Çini art, which has been carried on with the master apprentice relationship for hundreds of years, needs to be transferred to the younger generations with traditional and academic methods especially in terms of motif and pattern design.

Products:

Source: http://turkser.org.tr/seres18/docs/booklets/seres18.pdf